-

Fool About Me 3:030:00/3:03

-

0:00/5:29

Life is a big sea

full of many fish

I let down my nets

and pull.

-Langston Hughes, The Big Sea

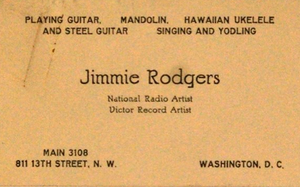

The moment he drove out of the new Holland Tunnel and saw Manhattan for the first time, he was sure his fortunes would soon make a turn for the better. From the roundabout, he merged onto Canal Street, stopping to ask the first sharp-dressed fellow he saw where he might find a top hotel near Times Square. I'm an entertainer you see. Here’s my new record for Victor…that's me, I'm Jimmie.

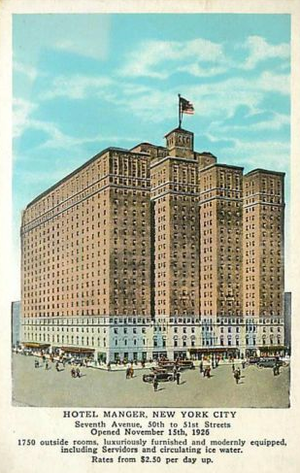

Turning the corner onto 50th Street between 6th & 7th Avenues, Jimmie feared he had been played for a rube when he saw not a hotel but the enormous Roxy Theater, the new 5,900 seat “Cathedral of the Motion Picture.” But the Roxy shared the block with the equally grand Hotel Manger--“the Wonder Hotel of New York”--which seemed like a fine spot for a new Victor recording artist.

Admiring the Roxy’s vaulted archways, he heard a paperboy call from the curb (“Times mister?) and Jimmie rolled down the window to give the kid two cents. Unfolding the paper on his lap, he pushed up the boater on his balding head and found the show listings on page 19 along with a notice for The Jazz Singer, which had opened at the Capitol Theater in October, the same week of Jimmie’s debut.

The damp November air smelled of coal, much like the railyards back home in Meridian. Poet Federico Garcia Lorca arrived in Manhattan from Madrid the following year and saw the city perhaps as Jimmie did:

four columns of mire

and a hurricane of black pigeons

splashing in the putrid waters...

Those who go out early know in their bones

there will be no paradise or loves that bloom and die

they know they will be mired in numbers and laws

in mindless games, in fruitless labors.

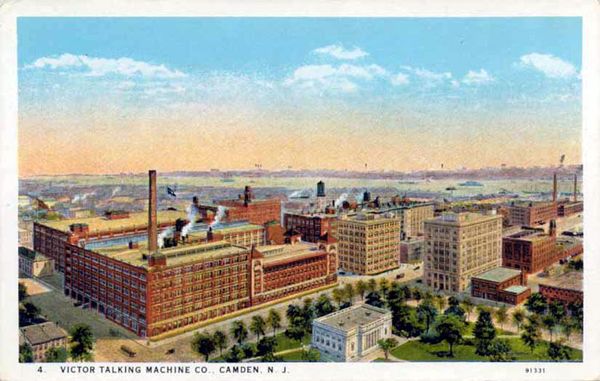

Watching the paperboy work the street with his bundle, Jimmie sang to himself, “I sell the morning paper sir my name is Jimmy Brown.” He was like that kid once---hustling for pennies in a ragged coat and cardboard brim hat. But even now with a record on Victor, perhaps the most reputable of record makers, Jimmie was not much better off in a second hand Dodge, virtually homeless, and broke but for $10 in his wool coat pocket his wife Carrie had saved from her waitressing job in a Washington D.C. tearoom. Since September they had been sharing her sister’s small house on 13th Street near Franklin Square while Jimmie marked time performing on radio or before the flickers at the Earle Theater waiting for an invitation to make a second record at Victor’s studio in New York.

The Victor distribution office in Washington had assured him that sales for "Sleep Baby Sleep" and "Soldier's Sweetheart" were promising for an unknown artist. But now two months had gone by without a word from Ralph Peer, the Victor rep who had recorded him in Bristol that summer. But as Jimmie assured Carrie over Thanksgiving, Mr. Peer was a busy man.

The Victor distribution office in Washington had assured him that sales for "Sleep Baby Sleep" and "Soldier's Sweetheart" were promising for an unknown artist. But now two months had gone by without a word from Ralph Peer, the Victor rep who had recorded him in Bristol that summer. But as Jimmie assured Carrie over Thanksgiving, Mr. Peer was a busy man.

Jimmie had worked tirelessly all his life it seemed to be discovered yet his session with Peer had come by chance. He had moved to Asheville to join a stringband he quickly renamed the Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers. On a trip to Bristol to buy the same Dodge he was driving now he learned Peer was in town holding auditions. By the time the entire group presented themselves for a tryout, Jimmie had quit—-or been kicked out-—over who should get top billing. “I was elated when I heard him perform without the unsuitable accompaniment,” Peer recalled. “It seemed to me he had his own personal and peculiar style and I thought his yodel alone might spell success."

Jimmie immediately sensed that he and Peer had much in common. Both were independent, intuitive, and at ease in all company. Perhaps, thought Jimmie, they also shared an ineffable feeling of destiny, which he had learned to smuggle through life for fear of derision or sabotage. Jimmie was thrilled, too that Peer had worked with some of his favorite artists like Fats Waller and Mamie Smith. “Jimmie bought records by the ton,” remembered Carrie.

Peer took note of Jimmie’s differentness, how his dark eyes focused on unseen places when he sang. His tone was smooth, clear, and conversational, as was his feeling for the blues, which was Peer's specialty.

Jimmie’s demeanor was an odd combination of mannerisms. He performed with one leg crossed over the other, and his unorthodox, strident rhythm went against the grain of his long, languid phrases. A New Orleans Times Picayune review of Rodgers noted “he plays a guitar as if he’d grown up with one on his lap and gags when he isn’t singing blue songs. You might call him a gentleman actor and he has a slightly different line than others in his profession.”

Peer was no stranger to artistic characters and was immediately intrigued. Jimmie wasn’t a superlative musician but he was a warm and engaging entertainer—perhaps, thought Peer—with his uncanny ability to fuse many kinds of styles at once in a single performance--Jimmie might be the kind of rural artist that could have national appeal with the right song. Peer suspected that Jimmie's boastful tales of success were an indication of not only his willingness to succeed but a deep desire to connect. Jimmie didn’t speak of his personal life--the loss of his mother to tuberculosis and a youth of solitary wandering. Or the death of his youngest daughter June Rebecca. But his friends recalled these shadows were ever present. And though it's unlikely Jimmie mentioned his own TB diagnosis three years before, Peer must have sensed he might be Jimmie Rodgers' last chance when their four-hour session produced only two selections.

Bristol wasn’t Jimmie’s first audition, either. The previous spring he had played for H.C. Spier in the back of Spier's music store on Farish Street in Jackson, Mississippi. Spier was a “talent broker” for Okeh, Victor, and Gennett, and would later recommend blues greats Charlie Patton and Skip James to the Paramount label. Spier advised Jimmie that he needed to write original material. That’s what Peer wanted, too, and so Jimmie was anxious to play Peer a new blues with those yodels he had liked so much.

Folding the Times, Jimmie got out of the car and took his Martin 00-18 from the back seat along with one of his records. He then stood for a moment, listening to the sounds of the city. Bowing his head against the afternoon chill, he started across the street toward the Hotel Manger.

Folding the Times, Jimmie got out of the car and took his Martin 00-18 from the back seat along with one of his records. He then stood for a moment, listening to the sounds of the city. Bowing his head against the afternoon chill, he started across the street toward the Hotel Manger. To calm his nerves, he imagined he might visit the C.F. Martin factory in Nazareth, Pennsylvania on his way home to see about a custom order, maybe with his name in mother of pearl. He had already introduced himself to the premier guitar makers that fall, writing in pencil: “I think you people make the best guitar in the world.”

To calm his nerves, he imagined he might visit the C.F. Martin factory in Nazareth, Pennsylvania on his way home to see about a custom order, maybe with his name in mother of pearl. He had already introduced himself to the premier guitar makers that fall, writing in pencil: “I think you people make the best guitar in the world.”

Carrie teased his efforts when she heard him seal the envelope with his customary pop of his fist. Mother (he called her) you don't understand. This is what you have to do when you’re an entertainer. That’s why he brought along the new business cards he printed in Washington, just in case he met someone that might prove helpful down the road.

The Hotel Manger’s black and white marble tiled lobby was lit from above by enormous crystal chandeliers hung from a 100-foot ceiling. Pursing his lips to swallow a cough roused from the heavy cloud of fine cigar smoke, Jimmie forced a grin as he strode to the long mahogany registration desk. A bellman looked him over with a raised brow.

Putting down his guitar, Jimmie calmly explained he was a Victor Recording Artist. You see, my debut sold 6,000 copies in the first month. They couldn’t wait to bring me up to phonograph again. Here, take one. I also need to place a call to Ralph Peer at the Victor offices in Camden. You can reverse the charges--Mr. Peer is expecting my call.

Peer was amused at Jimmie’s hustle and not only took the call but paid for Jimmie’s room, too. But Jimmie never had a doubt he would. "Aw shucks, Mother. I knew they were paying for it,” he told Carrie later. "Anyway, I figured they were a powerful firm and wealthy, and I was one of their artists. 'Course they'd want me to do 'em proud--and I did." And though Peer remembered he wasn’t so sure about Jimmie’s new “Blue Yodel” (“T for Texas”) he came to trust his protégé’s instincts. Within a few weeks of the release of “Blue Yodel,” Jimmie Rodgers from Meridian, Mississippi was a star.